Imagine a print distribution network with cloud-connected street vending/printer boxes. Overnight, algorithms API-shazam content for those boxes to print. Printed stuff piles up every night in those boxes, including cheap copies of a location-specific, regionally tuned catalog selling stuff for your normal, ordinary everyday life. This is TBD Catalog. It's an awkward attempt by an awkward business to attract more eyeballs and sell more stuff in a near future where the screen world has become so saturated and overrun that other mediums, like paper and street vending boxes, have become a natural spillover. It's a printed catalog you ritually pick up every morning to browse on your mostly boring, everyday ordinary driverless commute. You may even look forward to it, the way you look forward today to the free daily commuter news, or the Skymall catalog, or an entertaining bit of junk mail.

Its design fiction content is a bit new and weird. It portrays a different kind of future than you might have been used to. This is not your near future of superlative Silicon Valley exuberance where you happily 3D-print a perfect set of lease-licensed Opinel steak knives or blissfully commute to work in your fascistically sleek Google-powered, chem-battery fueled autonomous vehicles. Nor is this the abysmal near future where you huddle in the smoldering foxholes of apocalyptic ruin. TBD Catalog runs through the middle. It is neither extreme. It is a design fiction about a normal, ordinary everyday near future. TBD Catalog is a design fiction because it makes implications without making predictions. TBD Catalog is a design fiction because it sparks conversations about the near future. It serves to design-develop prototypes and shape embryonic concepts in order to discard them, make them better, reconsider what we may take for granted.

TBD Catalog shows us a world full of the end results of the work by a few Silicon Valley fellers who have ideas about fantastic new cloud-connected, wrist-controlled, multi-stack, API-rich, on-demand whatevers. TBD Catalog implies these worlds in their most normal, ordinary everyday form. Better than a CAD render or exuberant Kickstarter video, TBD Catalog tells the stories about these worlds complete with self-driving nanny cars, Panda Jerky, compute-intensive garden hoses, Internet-connected bathroom doors, selfie-refrigerators, soy-based hair combs, revolutionary underwear elastic band, Tweeting cat doors, on-demand, lovingly computed artisanal t-shirts, belt buckles designed on your phone and hand-crafted computer-milled wood saws. TBD Catalog tells the likely stories that no VC, no engineer, no modern pundit nor critic seems to be able to tell with any clarity about an Internet of Things, where everything is connected to everything — whatever that means. TBD Catalog tells stories about normal, ordinary everyday life in a near future world in which households have as many 3D printers as toothbrushes, each of which requires a permit for disposal of its excess material, waste, misprints and government mandated child locks to prevent printing choking hazards. TBD Catalog tells a story about a near future world in which crowd-contributed content has created the Number One ranked film franchise and nobody questions that everyone is a potential revenue-rich producer.

TBD Catalog is today's exuberance about a fantastic near future translated into its inevitably fraught, low-battery, poor reception, broken firmware, normal, ordinary, everyday sensibilities. It is neither boom, nor bust. It is just the near future now. It is the near future we'll wind up with for our sins. Welcome. Get yours.

TBD started out as a modest effort by our original core editorial team. There were 19 of us. We met in the city of Detroit in the United States to discuss what was jokingly referred to as the “State of Things” and to assess the future of products, their design and associated services as society evolved with its exuberance for cultures, businesses and daily rituals in which technologies and sciences played a central, defining role.

We were a disparate group of designers, curators, science fact and science fiction writers, students of science and technology studies, prototypers, cultural theorists, engineers, artists and makers. What brought us together was this commission from a quiet yet very successful venture group to consider the trajectories into the near future of the “big promises” of the day. Take the things that seemed liminal, the things in the laboratories, in the public media, in science-fiction films, in economic projections and then extrapolate these ideas and prototypes and make them into ‘things’ in the near future. But, specific kinds of near future things. Not hyperbolic perfections, but those things as they would exist as part of normal, ordinary, everyday life. If you stopped today and transported to the near future, what would the world look like? We assumed their objective was to assess a possible landscape of dozens of new ventures into which they could plow their billions (with a ‘b’). And, presumably they had a special foresight to anticipate the things that would become commodities rather than luxuries, as all great ideas eventually become, if they become anything at all.

To address this, we started by posing provocative questions to ourselves. How might the promise of what at the time was called an “internet of things” play out in the near future? What would the future look like in a world blanketed by advances in protection and surveillance technologies? If Autonomous Vehicle innovations continued its passionate race forward, what would it be to pick up the groceries, take a commercial airline flight, commute to work, have mail and parcels delivered, drop off the dry cleaning, meet friends at a bar across town, go on cross-country family vacations, or take the kids to sports practice or school? Would food sciences offer us new forms of ingestible energy such as coconut-based and other high-caloric energy sources, or caloric burners that would help us avoid exercise-based diets? In what ways would live, streaming, recorded and crowd-authored music and filmed entertainment evolve? How might advances in portable spring power hold up against traditional chemical battery power? How would emerging forms of family and kinship be reflected in social networks? How will Chinese migration to Africa shape that continent’s entry into the world of manufacturing, and how would that inevitability shape distribution and production economies? What is to become of open-source education and the over-supply of capable yet unemployed engineers? Would personal privacy and data hiding protocols be developed to help protect our families and businesses from profile pirates and data heists? What happens to our sense of social relations as today’s algorithmic analytic interpersonal relationship matchers get too good and algorithms effectively pre-pubscently “couple us off” before we have a chance to experience the peculiarities of dating life? Will crytocurrency disrupt today’s national currencies? What will become of coffee and plant-based protein products?

The Detroit Editorial and Conceptual Team: Aaron Straup Cope, Bruce Sterling, Cezanne Charles, Chris Woebken, Christian Svanes Kolding, Emmet Byrne, James Bridle, John Marshall, Julian Bleecker, Karl Daubmann, Marc Greuther, Marcus Bleecker, Meghan Mulholland, Moka Pantages, Nicolas Nova, Nick Foster, Raphael Grignani, Tom Bray, Zack Jacobsen-Weaver.

The Detroit Editorial and Conceptual Team: Aaron Straup Cope, Bruce Sterling, Cezanne Charles, Chris Woebken, Christian Svanes Kolding, Emmet Byrne, James Bridle, John Marshall, Julian Bleecker, Karl Daubmann, Marc Greuther, Marcus Bleecker, Meghan Mulholland, Moka Pantages, Nicolas Nova, Nick Foster, Raphael Grignani, Tom Bray, Zack Jacobsen-Weaver.

Our commission was to ask these questions and then represent the answers as design fictional services, evolutions of product categories and new kinds of social, domestic and retail experiences.

Effectively, we were charged with the task of taking a snapshot of the current state of our own 19-member collective consciousness. Within that snapshot would be certain initial, liminal ideas at some threshold of possibility or concern. We were then to extrapolate those ideas along a design fictional trajectory that would deliver it as a ‘normal ordinary everyday’ artifact - a product, service or interleaved formal or ad-hoc eco-systemic collection of thing - within some near future. Even the most hypothetical notion, the most speculative concern, was given room to air itself through discussion, sketching, testing, prototyping, debating and making. Some things we built in the normal sense of the word. Others, we hypothesized and constructed as immaterial props, inserting them into scenarios, stories and little moments in someone’s normal ordinary everyday life. Some services found their way into diegetic “treatments” - narratives that would up as moments in little films or microfictional stories.

Ultimately though, our task was to decant even the most preposterous idea through a series of design procedures that would make it as normal, ordinary, and everyday blasé as, for one retrospective example, the billions of 140-character messages sent into the ether each day - a form of personal individual communication that must have, at its inception, seemed to most of the world to be the most ridiculous idea ever. The point being that the most extraordinary preposterous social rituals have often made their ways into our lives to become normal and even taken for granted.

A report (or catalog, such as TBD) offers a way to normalize those extraordinary ideas and represent them as entirely ordinary. We imagined it to be a catalog of some sort, as might appear in a street vending box in any neighborhood, or in a pile next to the neighborhood real estate guides or advertising-based classified newspapers near the entrance to your local convenience store.

Why would we do this? Why would we be commissioned to produce such a “report”- and then pretend-present it as a catalog of things? Quite simply we did it as an alternative to traditional ways of imagining, constructing and discussing possible near futures. Rather than the staid, old-fashioned, bland, unadventurous “strategy consultant’s” report or “futurist’s” white paper (or, even worse - bullet-pointed PowerPoint conclusion to a project), we wanted to present the results of our workshop in a form that had the potential to feel as immersive as an engaging, well-told story. We wanted our insights to exists as if they were an object or an experience that might be found in the world we were describing for our client. We wanted our client to receive our insights with the shift in perspective that comes when one is able to suspend their disbelief as to what is possible.

How did we come to this state of affairs? During our workshop, we used a little known design-engineering concept generation and development protocol called Design Fiction. Through a series of rigorous design procedures, selection protocols, and proprietary generative work kits, Design Fiction creates diegetic and engineered prototypes that suspend disbelief in their possibility. Design Fiction is a way of moving an idea into existence through the use of design tools and fictional contexts that results in a suspension of one’s disbelief, which then allows one to overcome one’s skeptical nature and see possibility where there was once only skepticism or doubt.

There were a variety of tools and instruments we could put in service to construct these normal ordinary everyday things. For example, several canonical graphs used to represent trajectories of ideas towards their materialization would come in handy. These are simple and familiar graphs. Their representations embody specific epistemological systems of belief about how ideas, technologies, markets, societies evolve. These are typically positivist up-and-to-the-right tendencies. With graphs such as these, one can place an idea in the present and trace it towards its evolved near future form to see where its promise might end up.

We also had the Design Fiction Product Design Work Kit, a work kit useful for parceling ideas into their atomic elements, re-arranging them into something that, for the present, would be quite extra-ordinary. But, in the near future everyday, would be quite ordinary.

It is important to point out that we were not attempting to predict the future. Prediction felt far too hubristic and old fashioned. We wanted a more modern frame to put around our conversations - not to say what would be, but to set a stage that produced our insights with a modesty and humility. What we were striving to achieve was a kind of rich production design and a thorough visual-narrative context through which one might find some space to imagine, question, and extend the core characteristics of our insights into thought-provocations. We did not want to assume what would become the future and what ‘exciting’ technologies of the day would find their way into our lives, mindlessly disregarding the probably costs and consequences. We wanted to offer up a cast of props that could provoke conversations about what kind of futures we may want, and what kind of futures we may not want.

You might say that the catalog is wrong about this-or-that, or that it misrepresents a “trend” or misses an obvious near future product, or has got it all wrong. But then, this is what the catalog is meant to do - to encourage a discussion, debate, argument, wonderment as one might do in a book club or over a pint after a fantastic/good/middling/bad future-fiction movie.

No. Not prediction. Rather we were providing thought provocations. We were creating a catalog of things to think with and think about. We were creating a catalog full of creative inspiration for one possible near future - a near future that would be an extrapolation from todays state of things. Our objective was to create a context in which possible-probables as well as unexpected-unlikelies were all made comprehensible. Were one to do a subsequent catalog as a reflection on another year, it would almost certainly be concerned with very different topics and, as such, materialize in a rather different set of products.

The ideas to be extrapolated were quite varied, of course, given the diversity of our interests, professions, and where each individual’s attention had been focused over the year prior to the gathering. At the same time, the ideas were not typical flat-footed technological concepts that presupposed a trajectory to an object that might be expected in the typical utopic or dystopic sci-fi future - either the gleaming and bright future or the more familiar apocalyptic world end-state. There were no touch-interaction fetish things like e-paper magazines, no iPhones with bigger screens, no Space Marine Exo-Skeletons, no time-traveling devices, not as many computational screen devices in bathroom medicine cabinets as one may have hoped or feared. There was no over-emphasis on reality goggles, no naive wrist-based ‘wearables’, a bare minimum of 3D printer accessories. Where those naive futures appeared we debased them - we represented them with as much reverence as one might a cheap mass-produced lager, an off-brand laundry soap, or an electric toothbrush replacement head. We focused on the practicalities of the ordinary and everyday and, where we felt necessary, commoditized, bargainized, three-for-a-dollarized and normalized.

What was most interesting is that the deliverable - a catalog of the near future’s normal ordinary everyday - led us in a curious way to a state that felt rather like the ontological present. I mean, the products and services and “ways of being” were extrapolated, but people still worried about finding a playmate for their kid and getting out of debt. As prevalent as ever were the shady promises of a better, fitter, sexier body and new tinctures to prevent the resilient common cold. People in our near future were looking for ways to avoid boredom, to be told a story, find the sport scores or place a bet, get from here to there, avoid unpleasantries, protect their loved ones and buy a pair of trousers. Tomorrow ended up very much the same as today, only the 19 of us were less “there” than the generations destined to inherit the world designed by the TBD Catalog. Those inheritors, the cast of characters we imagined browsing and purchasing from this catalog in the near future, seemed to take things in stride when it came to biomonitoring toilets, surveillance mitigation services, luxurious ice cubes, the need for data mangling, living a parametric-algorithmic lifestyle, goofy laser pointer toys, data sanctuaries, and the inevitable boredom of commuting to work (even with “self-drivers” or other forms of AV’s.)

We supposed this was the point of the “normal ordinary everyday” aspect of our Design Fiction brief: the consideration that the near future, even as a designed fiction, is a construct as normal as any other. The near future comes pre-built with the expectation that, being the future, it must be quite different from the vantage point of the present. This is an assumption we were trying to alter for a moment - the assumption that the future is either better or worse than the present. Quite less often is the future represented as the same as now only with a slightly different cast of characters. Were we to take this approach, which we did, it would be required that the cast of characters from the future would be no more nor less awestruck by their present than we are today awestruck by the fact that we have on-demand satellite maps in our palms, that the vapor trail above us is a craft with hundreds of souls whipping through the stratosphere at breakneck speeds, and that when we sit down at a restaurant fresh water (with ice) is offered in several varieties from countries far away, with or without bubbles.

This imagined central cast of TBD Catalog readers would need to accept the “present day” of the catalog in an almost blasé way. Equal to that central cast of characters might be the outliers - their grandparents, for example - who have the stereotypical, rueful opposition they are destined to have - never quite understand “that music kids are listening to nowadays”, or “why the kids are wearing such saggy-baggy trousers that barely hang on their waist”, etc. (A stereotype to be sure, but not entirely without merit and utility in the context of setting a mood and playing an archetype for the benefit of sustaining the design and the maneuvering the fiction in and around the artefacts themselves. This is the diegesis — the narrative that is supposed, implicated and fashioned through the reading of the catalog itself.)

It was important that the concepts be carefully represented as normal, rather than spectacular. Were things to have a tinge of unexpected social or technical complexity as suggested, for example, by regulatory warnings, a hint of their possible mishaps, an indication that it may induce a coronary or require a signed waiver — all the better as these are indications of something in the normal ordinary everyday. This is not to suggest that the future may be bleak in the dismal pessimistic sense. It is just that the near future may probably be quite like the present, only with a new cast of social actors and algorithms who will, like today, suffer under the banal, colorful, oftentimes infuriating characteristic of any socialized instrument and its services. I am referring to the bureaucracies that are introduced, the jargon, the new kinds of job titles, the mishaps, the hopes, the error messages, the dashed dreams, the family arguments, the accidental data leak embarrassments, the evolved social norms, the humiliated politicians, the revised expectations of manner and decorum, the inevitable reactionary designed things that reverse current norms, the battalions of accessories. Etcetera.

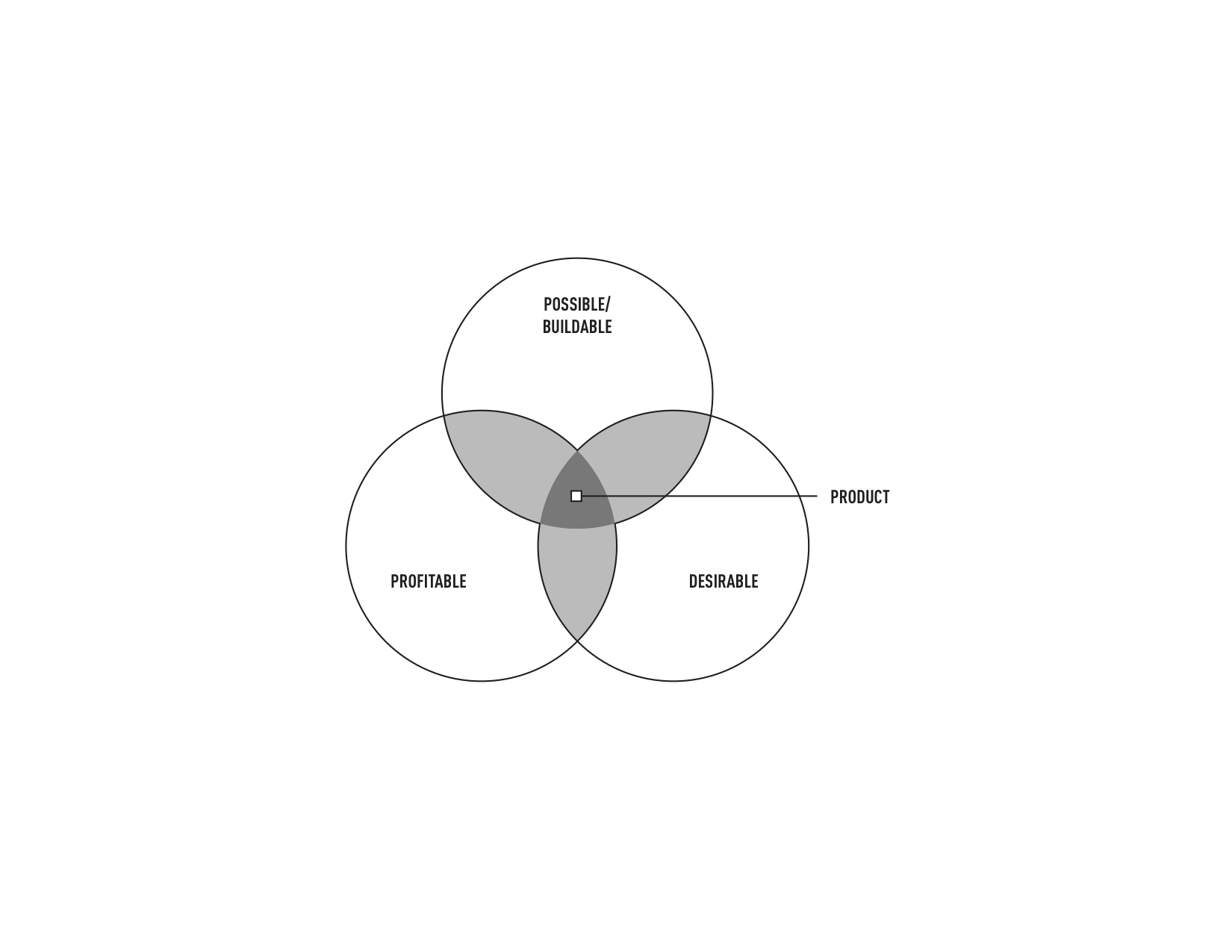

Also, concepts often started as abstract speculations requiring deciphering and explication. These would need to be designed properly as products or services that felt as though they were well-lived in the world. Predictive design and speculative design lives well in these zones of abstraction. To move a concept from speculative to design fictional requires work. To materialize an idea requires that one push it forward through the gauntlet any design concept must endure to become the product of the mass-manufacturers process of thing-making. To make an idea become a cataloged, consumable product in the world requires that it be manufacturable, desirable and profitable. Each of these dimensions in turn require that, for example, the thing be imagined to have endured regulatory approvals, be protected as much as possible from intellectual property theft, be manufactured somewhere, suffer the inevitable tension between business drivers, marketing objectives, sales goals and design dreams while also withstanding transcontinental shipping, piracy of all kinds, the CEO’s wives color-choice whims (perhaps multiple CEOs over the course of a single product’s development) and have a price that is as cheap as necessary in many cases but perhaps reassuringly expensive in others. Things need to be imagined for their potential defects, their inevitable flaws and world-damaging properties. A product feels real if it has problems it mitigates as well as new, unexpected problems it introduces. Things need names that are considered for certain categories of product, and naive or imbecilic for others. Things need to be imagined in the hand, in use in “real world” contexts - in the home, office, data center, one’s AV, amongst children or co-workers. They should be forced to live in their springtime with fanfare, and their arthritic decline on the tangled, cracked and chipped 3/99¢ bin. To do this requires that they live, not just as flat perfect things for board room PowerPoint and advertisements, but as mangled things co-existing with all of the dynamic tensions and forces in the world.

This is a small bit of what it is to employ Design Fiction — the things that exist in the world rather than the things that exist as a concept in an abstraction of the world such as in a Cornell Box-like environment.

But, Design Fiction was never just about speculation, nor only about creating film and video representations using green screen special effects and planar tracking plug-ins. More importantly, whatever form or genre of representation one uses, Design Fiction is about creating provocations, about prodding ideas to make them thorough, considered, alive and in-the-world. It is about activating the imagination, providing seeds of inspiration and insight. Design Fiction is about shifting one’s sense of what is possible by making the extraordinary feel ordinary.

Although Design Fiction relies on fictional tropes imbued in richly physical (visual, material, tactile) “props” - what we call the “diegetic prototype” via David Kirby (‘Lab Coats in Hollywood: Science, Scientists, and Cinema’ is David Kirby’s canonical reference to this notion), its real effectiveness comes from its ability to de-prioritize the thing and re-prioritize the lives that experience the thing, in all its challenged glory, in all of the contingencies of existence, in its inevitably flawed (however slight) character.

Ultimately, things are an embodiment of our own lived existence — our desires and aspirations; our vanities and conceits; our servility and humility. A Design Fiction catalog of things becomes an epistemic reflection of the times. One might read such a catalog as one might read a statement titled “The Year In Review” - a meditation on the highlights of a year recently concluded. This would not be prediction. It would be a narrative device, a form of storytelling that transcends naive fiction to become an object extracted from a near future world and brought back to us to consider, argue over and discuss. And, possibly, do again as an alternative to the old journalistic “The Year In Review” trope. Is there a better name or form for the thing that looks forward with modesty from today and captures what is seen there? What do we call the thing that stretches into the near future the nascent, barely embryonic hopes, speculations, hypotheses, forces, political tendencies - even the predictions from those still into such things? Is it Design Fiction? An evolved genre that splices together naive fiction, science-fiction, image-and-graphic mood boards and the now ridiculously useless ‘futurist’ predictions and reports? Something in between crowd-funding as a way to prototype a DIY idea and multiform, transmedia shenanigans?

Without a clear strategy, we ended up with what is here now. Although in the end, what we designed became a veiled report on the normal everyday ordinary near future based on the course of trajectories our tools pointed us towards. The thing is - through a quirk of material, visual and graphic design - the report was all too easily confused for a proper product catalog. We take this as a quirk to be sure, but a fortuitous one based on our enthusiasm to design as much as write. This along with our reluctance to deliver our insights in sad old PowerPoint would lead to what TBD Catalog has become.

What happened is this: the first “report” - because it was more a commissioned report on the near future than a catalog - had limited circulation, but copies were distributed by some recipients to others without annotation or context. TBD Catalog Issue 1 went viral in a humble sort of way. It was circulated much wider than initially anticipated. Many people who received it second or third hand could be easily forgiven for mistaking it as an actual product catalog.

What happened next was truly bizarre. We started receiving inquiries from individuals around the world who wanted to order items and provide crowd-funding style financial backing for product concepts. Some entities demanded licensing fees because a product the “catalog” purported to “sell” was something they had already developed and were selling themselves or, in some cases, they had even patented and so were notifying us that they would pursue legal remedies to address our malfeasance.

We found that products and entire service ecosystems we implied through advertisements actually existed in an obscure corner of the business world. Of course, there were items in the catalog that we knew existed already. In those cases, our task was not to re-predict them, but to continue them along their trajectory using one or a combination of our graphs of the future (see following pages). In these cases, it can be expected that an unwitting reader of TBD Catalog would naturally make contact with us to find out why they had not be made aware of the new version of the product, how could they get a discounted upgrade, or how they could download the firmware update for which they simply had not already been aware.

Overwhelmed by this response, we realized that our “report” was actually a guide to a world that existed in a curious “atemporal”* state, a curious attribute of Design Fiction.

Time was out of itself. Much of the world was (and arguably sustains itself by remaining) in an atemporal state. Things we fictionalized as already designed, already existing, already everyday ordinary normal boring products may or may not exist. Either way, at a minimum the designed products felt consistent with the current state. The TBD Catalog became a kind of atemporal document of things imagined to exist, existing, probably on the verge of existence, in the state of becoming real in some laboratory, being tinkered with in a maker’s basement, the topic of whispered discussion between some engineers and venture capitalist-entrepreneurs, etcetera.

This is what TBD Catalog has become. A catalog of the normal everyday ordinary from today’s atemporal present for tomorrows atemporal future.

More important than this peculiar turn of events is what this productive and through-provoking confusion implies: the Design Fiction process has real value as a decision-making tool. How does this process become a decision-making tool? It becomes a tool through its ability to present things that could be and allowing them to create their own context, to “speak” about the world in which they exist, to describe their own world however indirectly, however implicitly. One could write quite didactically about innovation of such-and-so, or make a prediction of some sort or commission a trend analysts report or a clever name-brand futurists’ speculation. Or, one could start with the names of some things and fill out their descriptions at their “consumer face” and let the things themselves come to life, define the sensibilities of those humans (or algorithms?) that might use them. How would those things be sold - what materials? what cost? what consumer segment? Three-for-one? Party colors? Or one could do a very modern form of combined prototyping-funding such as the ‘Kickstarter model’ of presenting an idea before it is much more than a collection of pretty visual aids and then see what people might pay for an imaginary thing. Design Fiction is the modern form of imagining, innovating and making when we live in a world where the future may already have been here before.

Let’s just remind ourselves of the peculiar modern world we were in when the exercise began some years ago. We faced a world in which “the future” was upon us in an extraordinary way. This was not the world with a calm, clear, well-understood mid-century modern trajectory to a future of jets, space travel and kitchen conveniences. Things were not always just getting more chrome nor always smaller and more compact. People were Tweeting cultural revolutions, for goodness sake. Things were changing, new things were coming into existence, old companies were being positively swallowed by the spunky, sparky ideas of a few kids in an old apartment who presented their “idea” based on a photo realistic computer aided design rendering along with some earnest, carefully edited video of their aspiration cut to mandolin-heavy tear-jerker music - and a plea for the world to pre-order expensive t-shirts that might, just possibly also result in getting the thing they dreamed to make. And they would get millions of dollars ahead of anything real being created. These were dreamers to be sure, and dreamers who happened to live within a world that would pre-pay for their ambitious goals as represented as - let’s face it - aspirational visual and narrative fictions.

Many of the TBD Catalog items exist in this thick nebulae of things that could be, things coming into being and things that have been for quite some time. It can be read as a desk reference to a near future’s technologies. Or think of it as a field guide to the democratized, everyday-ordinary aspirations, concerns, problems, ambitions of some multivalent near future cultures. Perhaps it is a production designer’s prop-list for a story set to take place in another time. Or a story teller’s inspirational source book to help “fill out” their narratives with accoutrements, plot devices and MacGuffin’s. Or a film maker’s “bible” canonizing the general themes, rites, rituals and norms of a world they intend to narrate. TBD Catalog may be a probe into a world which sends back symptoms of itself - its rituals, its discomforts, its ways of being - in the form of the things it makes for itself.

But the probe is only half of the exercise. We want to discover for ourselves what to do next before we do what’s next. Design Fiction approaches the challenge of innovation, of doing something new and exciting and unexpected by stretching out towards the unspecified time when that thing becomes pervasive and blasé. It’s a kind of prototyping that TBD Catalog performs, although more diegetic prototyping than engineering prototyping. Other kinds of Design Fictions compel us to prototype and test a near future by writing its product descriptions, filing bug reports, creating product manuals and quick reference guides to probable improbable things. This is a different way of innovating, of thinking-through new things than the old-fashioned innovation techniques.

We apologize in advance for not fulfilling the desire for perfect harmonized futures or decrepit rusted toxic futures. Instead we created the debased product future in which the exuberance surrounding 3D printers, Apple’s immaculate design, the internet of things, targeted advertising, BitCoin and the algorithmic way of life is tamped down quite some bit. We didn’t do this out of a reluctance to accept that these things aren’t real. We did it because we recognized that change happens and, although these things may well be a little pebble in the bedrock of that change, they will not sustain their exuberant, hyperbolic role. They will rust and wear and flail. They will cause bubbles that will burst all over themselves. Therein lies the curious, weird gaps, and holes and opportunities that are often overlooked because exuberance introduces a rather narrow-naive vision of what those things look like in the near future. Design Fiction as we did here forced us to stretch that exuberance until it broke down and 3D printers were as mundane as fresh news printed on paper and delivered daily to your doorstep; as middleclass-deomocratic as drinkable water coming out of a tap to boil for a morning coffee; as un-noteworthy as being able to have a video chat with someone from your palm. When you do that, the world shifts just a bit, rights itself again, and you begin to find more of a compelling “truth” to that near future: will landfills overflow with bad and broken 3D plastic prints from your neighbors attempt (again) to make a dining room table? When the first kid chokes on a small part, will legislation incite a public debate about 3D printer-operator licensing, permits and material usage quotas? We don’t do this because we are “against” 3D printers, or autonomous flying robots, or a world of connected dresser drawers. (It makes as much sense to be against such things as to be against breakfast. Some breakfasts are have normative value.) We do this Design Fiction approach because it seems more persuasive and more thought-provoking and enlightened to consider that change eventually normalizes out to, well - become normal ordinary everyday. Change makes room for change again. And therein lies the more engaging, provocative, mindful and fun discussions about what those optimistic futures become in the everyday. It is a more telling story about the future than a purely optimistic white paper prediction. Is is anathema, in a good way, to the typical hubris of the ‘serial entrepreneurs’ to create disruptions just ‘cause’, implications be-damned.

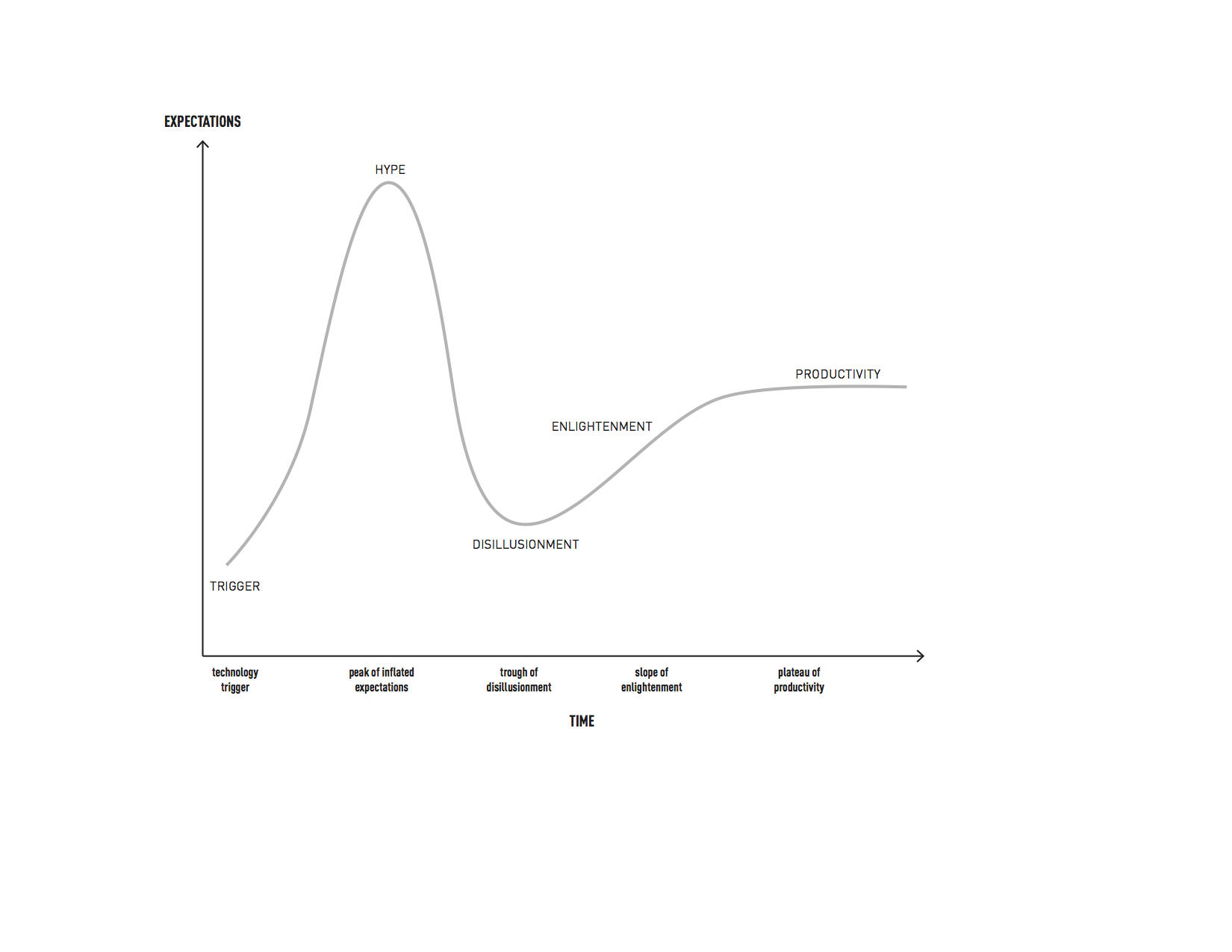

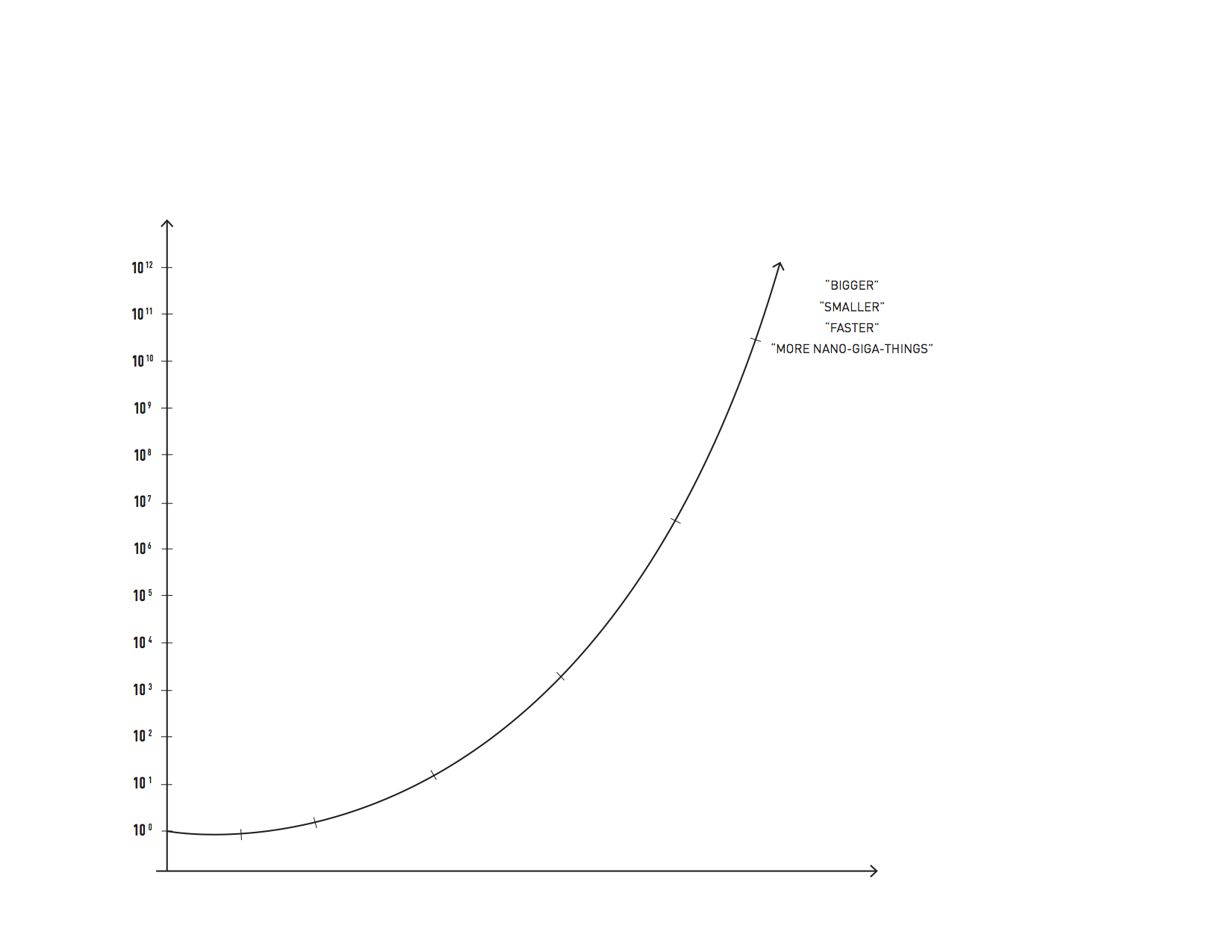

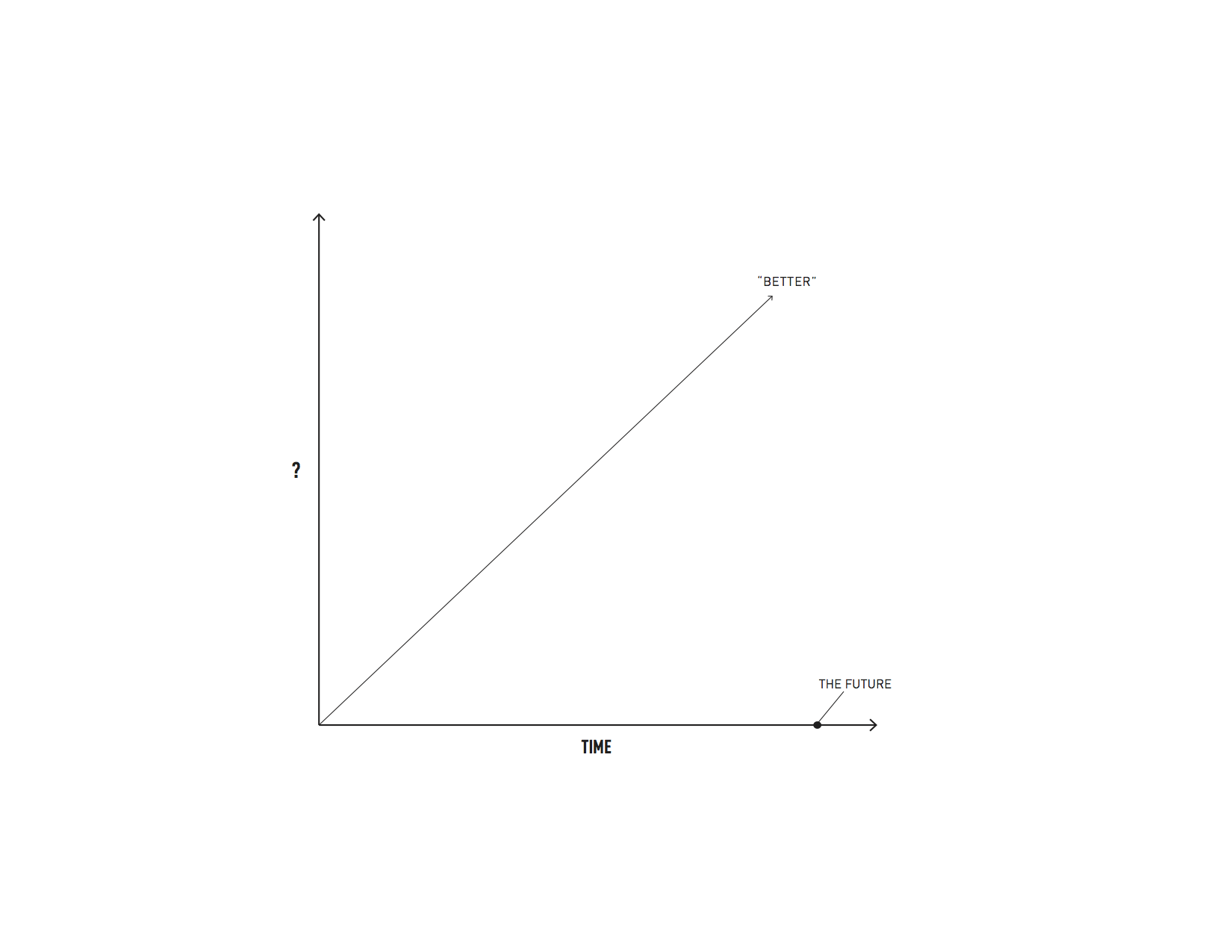

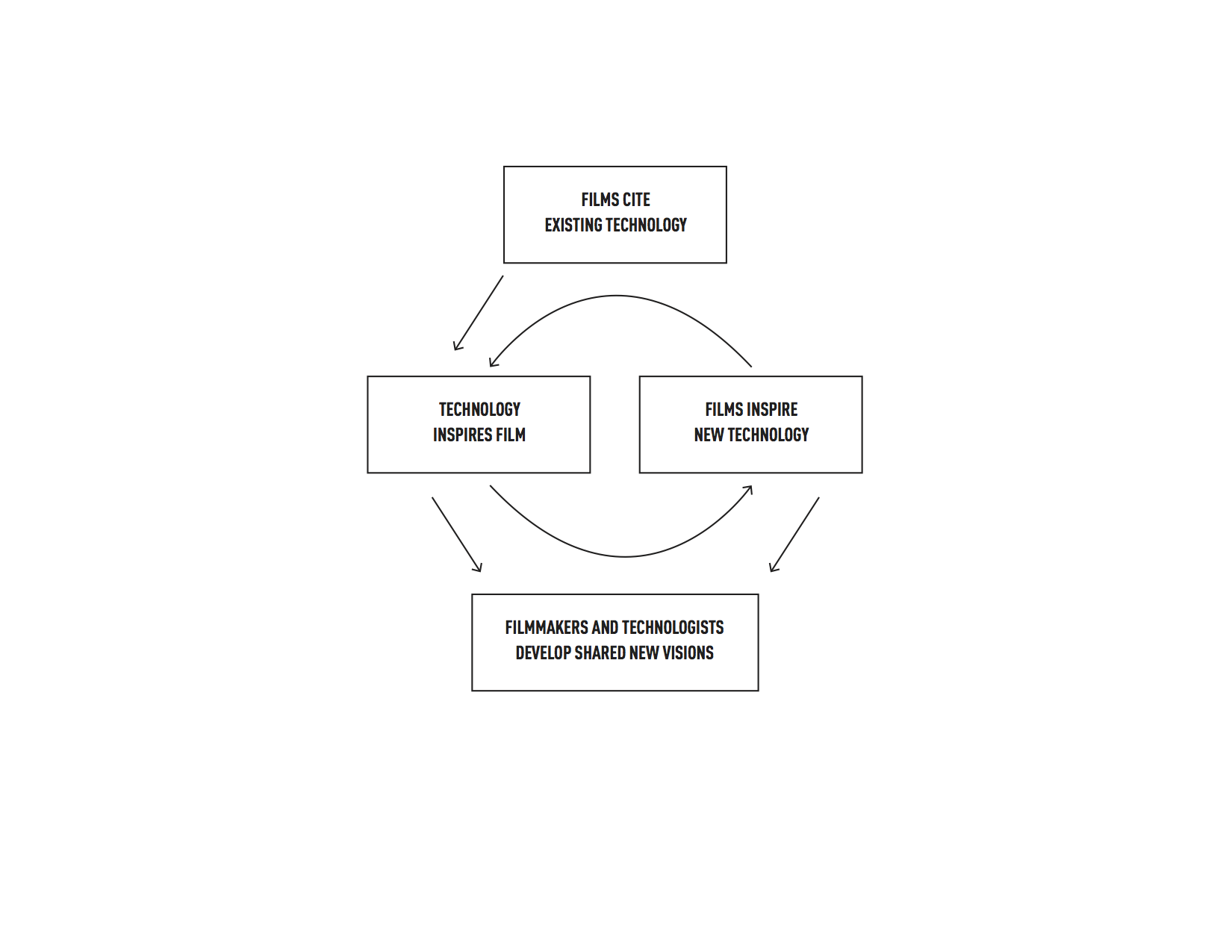

The products we created - well, these are not the only things that might exist of course - this is a form of near future fiction from a group of 19 people. But they are the things that our brief exhaled, as all design briefs do. They create things that start one thinking about what could be. They are thought-provokers, conceptual starters, seeds of but one near future world. They were situated at various near future points on the Garner Hype Curve, or the exponential-optimistic graph of Moore’s Law, or the sweet spot of the Product Design Venn Diagram. And from there these things spoke to us about their world, giving us an insight into the fuller contours of it, forcing us to consider how precisely they might all co-exist in a cacophonous product-service world ecology. These products told us about the world and they themselves produced even more future concepts, technical possibilities and social, political and cultural stories.

We found some of the themes these product-provocations implied - the algorithmic way of life, parametricization, dataflage, food genehacking, cultural migrations, shifts in sites of manufacturing. There were surprises: autonomous vehicles are routine to the point of boring; it’s an expensive privilege to erase or camouflage one’s life-long data trail; paper printed things exist as a counterweight to the overwhelming density of digital media. And more. You find all these things, the description of this world here in this edition of TBD Catalog. Read it as a kind of anthropological excavation, an inventory of things and then read between the lines to see the kind of worlds you might anticipate and their implications.

fig. a: Gartner Hype Curve traces outrageous ideas from excited trigger moments through frenetic hype (typical in media outlets) to inevitable sad disillusionment to refinement of what is actually sensible finally to mundane product/ion. Oftentimes the principle is reflected differently at the trigger point and final possible-profitable-desireable productivity point. For example, personal autonomous transportation as a trigger principle as represented as personal jet pack and finally reflected in its viable form as on-demand autonomous vehicles.

fig. a: Gartner Hype Curve traces outrageous ideas from excited trigger moments through frenetic hype (typical in media outlets) to inevitable sad disillusionment to refinement of what is actually sensible finally to mundane product/ion. Oftentimes the principle is reflected differently at the trigger point and final possible-profitable-desireable productivity point. For example, personal autonomous transportation as a trigger principle as represented as personal jet pack and finally reflected in its viable form as on-demand autonomous vehicles.

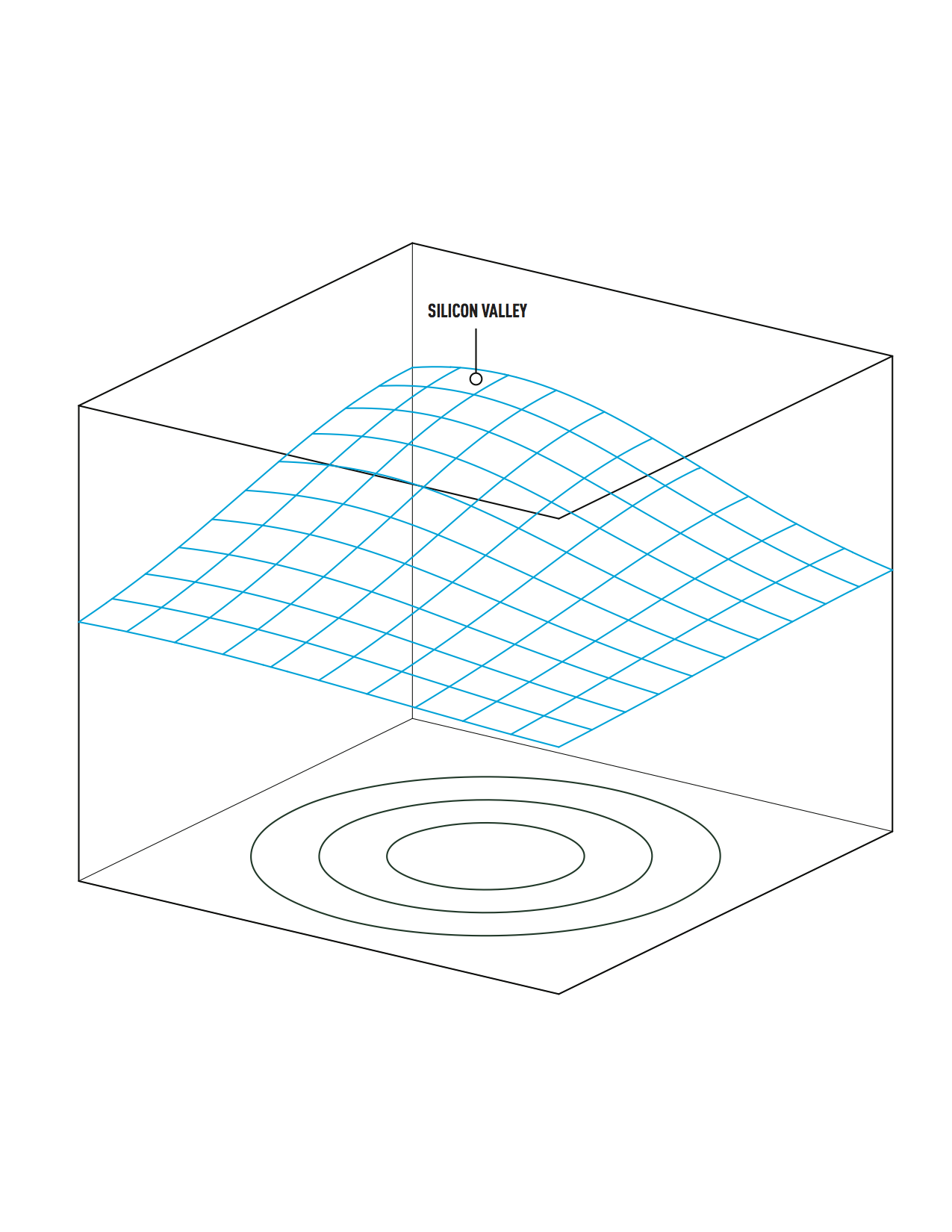

fig. b: The Unevenly Distributed Future Graph represents an interpretation that “the future” is geographically rather than temporally situated, existing in and about Silicon Valley in the Far West United States. Regions situated further away (as the crow flies) from the center of this geo-future may exist moments, or even months behind and are therefore temporally disenfranchised/ disabled from leasing the newest cloud- based services, installing the latest apps, participating in the coolest betas, joining companies before the series C or even mezzanine financing round, purchasing the handiest networked objects, eating the tastiest generipped produce, scanning the latest news updates, etc. In some cases, the geographically furthest regions may never experience the future either because of bad licensing agreements or the political, social or cultural hubris of the Silicon Valley Keiretsu.

fig. b: The Unevenly Distributed Future Graph represents an interpretation that “the future” is geographically rather than temporally situated, existing in and about Silicon Valley in the Far West United States. Regions situated further away (as the crow flies) from the center of this geo-future may exist moments, or even months behind and are therefore temporally disenfranchised/ disabled from leasing the newest cloud- based services, installing the latest apps, participating in the coolest betas, joining companies before the series C or even mezzanine financing round, purchasing the handiest networked objects, eating the tastiest generipped produce, scanning the latest news updates, etc. In some cases, the geographically furthest regions may never experience the future either because of bad licensing agreements or the political, social or cultural hubris of the Silicon Valley Keiretsu.

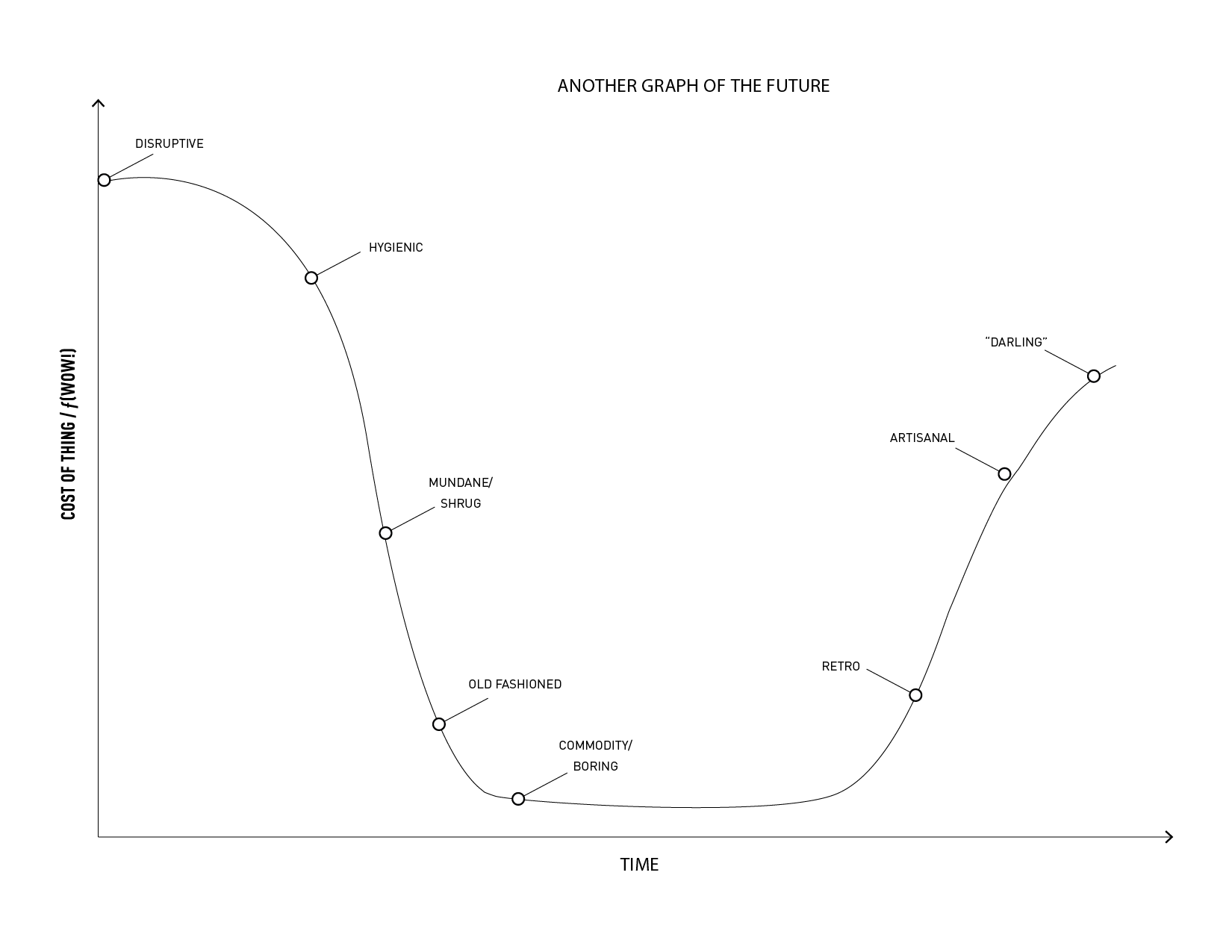

fig. h: A useful projective graph that traces a disruptive idea straight down through common/everyday/ordinary and eventually to old-fashioned/quaint. An extremely small minority of things experience a second life as retro, artisanal and even ‘darling’ revivals. For example, film cameras, regional lagers, external frame backpacks, calculator watches, luggage without wheels.

fig. h: A useful projective graph that traces a disruptive idea straight down through common/everyday/ordinary and eventually to old-fashioned/quaint. An extremely small minority of things experience a second life as retro, artisanal and even ‘darling’ revivals. For example, film cameras, regional lagers, external frame backpacks, calculator watches, luggage without wheels.

fig. d: Moore’s Law applied generally to things that may be suggested to advance at exponential rather than linear rates, e.g. battery life, screen size, display resolution, bandwidth, time between reboots, genetic density, printer dimensions, etc.

fig. d: Moore’s Law applied generally to things that may be suggested to advance at exponential rather than linear rates, e.g. battery life, screen size, display resolution, bandwidth, time between reboots, genetic density, printer dimensions, etc.

fig. e: Canonical “up and to the right” graph that represents anything today as only getting more-so over time, eg more pixels, faster network, robustity, eco-systemic, lighter/heavier, bigger/smaller, faster/more-thoughtful. Variant of the “Moore’s Law” exponential growth for more modest speculations.

fig. e: Canonical “up and to the right” graph that represents anything today as only getting more-so over time, eg more pixels, faster network, robustity, eco-systemic, lighter/heavier, bigger/smaller, faster/more-thoughtful. Variant of the “Moore’s Law” exponential growth for more modest speculations.

fig. f: A graph representing the curious interplay of entertainment, story, visual production and a mass audience. A film can introduce a sci-tech concept that may or may not exist in fact (research notion, liminal concept, loosely understood principles, experiments), e.g. “..I want to make something like that Star Trek communicator I loved when I was a kid, but I’m going to call it, The Celluar Phone.” Alternatively, a sci-tech project takes cues from or leverages a better told story about a concept in development to use as an indexical example, eg “We are pleased to announce that the US Department of Defence has contracted us to provide this nation’s Space Marine’s with our latest tactical product — The Ripley Exoskeleton.”

fig. f: A graph representing the curious interplay of entertainment, story, visual production and a mass audience. A film can introduce a sci-tech concept that may or may not exist in fact (research notion, liminal concept, loosely understood principles, experiments), e.g. “..I want to make something like that Star Trek communicator I loved when I was a kid, but I’m going to call it, The Celluar Phone.” Alternatively, a sci-tech project takes cues from or leverages a better told story about a concept in development to use as an indexical example, eg “We are pleased to announce that the US Department of Defence has contracted us to provide this nation’s Space Marine’s with our latest tactical product — The Ripley Exoskeleton.”

fig. g: Possible Profitable Desirable, a graph useful for defining an idea as a product which must work the tension between

these three dimensions. It works under the assumption that all such things known as products must exist in the sweet spot — the center — in order to be viable in a general marketplace. Thus, one must describe or represent a viable product as having equal measures of all three dimensions either. It should be noted that any product can be fictionalized as existing in that center through a variety of Design Fictional techniques, including compelling advertising design and copy, hypothetical bug reports, user forum discussions, images of the product extant e.g. in the hand, at a point of purchase display, in a catalog, broken at a trash heap, for sale at a flea/farmer’s market, represented on a promotional t-shirt, as a laptop sticker, indicated as extant based on a car-side magnetic sticker offering at-home or in-office service & repair for said product, etc.

fig. g: Possible Profitable Desirable, a graph useful for defining an idea as a product which must work the tension between

these three dimensions. It works under the assumption that all such things known as products must exist in the sweet spot — the center — in order to be viable in a general marketplace. Thus, one must describe or represent a viable product as having equal measures of all three dimensions either. It should be noted that any product can be fictionalized as existing in that center through a variety of Design Fictional techniques, including compelling advertising design and copy, hypothetical bug reports, user forum discussions, images of the product extant e.g. in the hand, at a point of purchase display, in a catalog, broken at a trash heap, for sale at a flea/farmer’s market, represented on a promotional t-shirt, as a laptop sticker, indicated as extant based on a car-side magnetic sticker offering at-home or in-office service & repair for said product, etc.

Near Future Laboratory is a thinking, making, design, development and research practice based in California and Europe

Our goal is to understand how imaginations and hypothesis become materialized to swerve the present into new, more habitable near future worlds. Our practice involves working closely with creative, thoughtful experts within various domains of work depending on the needs of any particular project. Our associations with a wide network of well-respected and accomplished practitioners makes it possible to work from concept development to construction of unique digital designs.

www: nearfuturelaboratory.com | email: info@nearfuturelaboratory.com | twitter: @nearfuturelab